My hometown is well-known for three things: A casino, “world-famous” caramel rolls (worth the stop at Tobies Restaurant or Gas Station, but I recommend the fried rolls with white frosting), and, of course, the Great Hinckley Fire.

If you've traveled north from the Twin Cities (perhaps to Duluth or the North Shore), you’ve likely stayed close to the interstate to gas up and get food. Travel a mile east or west, however, and you might stumble upon the Hinckley Fire Monument (east) or the Hinckley Fire Museum (west).

As a youth of about 11 or 12, I spent two summers helping my cousin volunteer at the museum. Yep- while other middle schoolers were rollerblading or swimming on summer vacation, I was cleaning artifact display cases and giving short speeches to tourists about a disaster that killed hundreds of people. (I honestly wouldn't have had it any other way- preteen Sadie loved this stuff as much as adult Sadie does). It was during one of these summers that I learned a sad story regarding the mass graves of the fire victims.

The Trenches

Located just a bit east of I-35, the Hinckley Fire Monument stands over fifty-one feet tall in the Lutheran Memorial Cemetery. It was dedicated on September 1, 1900, exactly six years after the 1894 disaster. The official statistics of the fire state that over 200,000 acres were burned and between 418-476 people were killed. This number likely did not include many Native people who were killed in the fire, among other individuals who lived in rural areas.1 About 248 victims were buried in four long, narrow mass graves just east of the town center (sometimes called "the trenches" or "mounds" by locals).

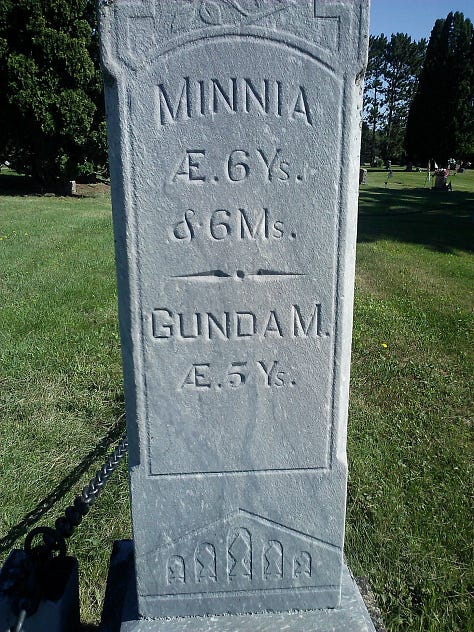

Take a look at that previous photo. The mounds aren't easy to see in the photo, but in person, they're pretty distinct. Now look at the chain fence around the mounds. See the one headstone on the left...? Inside the fence?

When I volunteered at the Fire Museum, I was told that a man who lost his entire family in the fire had this stone placed inside the fence of the trenches. He knew his family was in the mass graves, and decided that when he died, he wanted to be buried as close to them as possible.

So... was this story true? Who was this man, and who were his family members who perished in the blaze?

Hans Paulson

The first part of this mystery was easy to investigate. The names on the stone mention that H. Paulson was the family patriarch. Hans Paulson was born about 1855, possibly in Norway. Hans eventually settled in Eau Claire, Wisconsin. His wife was Berthe Marie Vestby (later known as Maria). While in Wisconsin, the couple had three children: Minnia born 1888, Gunda, born 1889, and Paul Alfred, born 1892. Daughter Hanna was likely born in Hinckley in 1893.

Hans in Hinckley

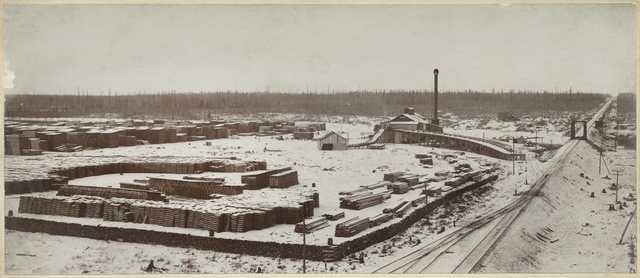

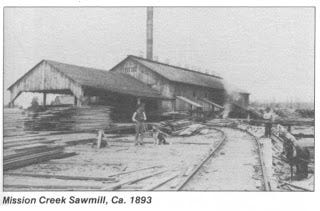

The promise of a steady income may have led Hans to the booming lumber industry in Hinckley sometime before 1894. He was employed at the Brennan Lumber Mill after the family moved to Minnesota.2 The mill was arguably the largest employer in the town, with upwards of 300 men working there by 1894.3 The area was rich with timber, which was in high demand both in Hinckley and down the river to the Twin Cities. Lumbermen worked quickly, cutting down trees and leaving the branches (“slashings”) behind in order to harvest as many logs as possible each day. Piles of thousands of branches, plus a very dry summer, led, in part, to the widespread fire on September 1, 1894.

Fire

Hans was working at Brennan Mill when the fire approached the lumberyard. Once flames were in sight, it was all hands on deck for the employees: The only fire system in place was barrels of water set along the roof. It soon became clear that the fire was far too powerful for such primitive safety precautions. The mill was destroyed and its owners suffered hundreds of thousands of dollars in losses.4

Most of the millworkers lived nearby with their families, and it is believed that "many of the [workers] were fighting flames at the south side of the village and were cut off from their homes by a wall of fire."5 The families likely ran for water or cellars for escape, with varying levels of success. Hans' wife and children took refuge in a swamp just northeast of the mill. Over 100 people perished in that swamp: Hans' wife and four children included.6

Searching for Family

In the aftermath of the blaze, reporters flocked to the ruined town to interview survivors. One met Hans, who seemed in shock from the events of September 1st. Unable to find his family after the fire had abated, Hans headed to the area where the dead were being identified and buried (what would eventually become the trenches). He told the reporter, "I am going out to the cemetery to see if I can find my wife and four children. I lost them all."7

Once at the burial grounds, a rainstorm commenced. Volunteers were digging the trenches in sheets of rain, and families of missing people were scanning rows and piles of human remains for any familiar faces or belongings. Hans searched for any sign of his wife and four children. It was nearly impossible to identify victims, as most were burned beyond recognition. Hans persevered, however, and eventually found one of his daughters. She was identified only by small bits of her white clothing. A reporter noted the dreadful scene and left before Hans found any of his other children or wife.

Moving On

Upon further investigation, I learned Hans was not actually buried near his family. His name is mentioned in the headstone only in relation to his family- his death date is not carved on any of the four sides. His death date and location are a mystery.

After the fire, Hans was quite literally "alone in the world," as one paper later commented.8 While fighting the fire at Brennan Mill, Hans left his wife and children in the care of his wife's brother, Thomas Westby. Thomas, his wife, and their five children were found deceased in the same swamp where Hans' family died.9 It is unknown where Hans lived after the fire, or if he ever remarried. He may have returned to Eau Claire, as he still owned a small dwelling there. 10

Hans may have commissioned the headstone for his wife and children. I think it is more possible, though, that it was paid for via donations. Hans' story was published in newspapers around the world after the Hinckley Fire (the story made papers as far away as Australia). Perhaps someone touched by the family's tragic story paid for the stone. Though Hans was not buried near his family, the marker is a beautiful memorial to his wife Maria and their children Minnia, Gunda, Paul, and Hanna.

The New York Times, 4 Sep 1894

Hinckley Fire Museum “Facts & Timeline”

The Great Hinckley Fire-1894, MN Dept of Natural Resources

Swenson, From the Ashes, 34.

Ibid, 31; Access Genealogy

The New York Times, 4 Sep 1894

The Upper Murray and & Mitta Herald, 25 Oct 1894

Ibid; Hinckley Fire, Minnesota Cemeteries

Chicago Tribune, 5 Sep 1894

As a kid on my way to Luther League camp, we'd stop at Tobie's on the way. That Hinckley was famous for the fire didn't interest me until I was much older and could appreciate the scope and sweep of the tragedy. The story of Hans Paulson and the search for his family is a great way to convey the magnitude of devastation.

I drive by the Hinckley cemetery with the fire memorial every summer weekend - on the way to and from our cabin in Wisconsin. As a junior high student, our class took a trip to the nearby state park and along the way we visited the memorial and learned some of the history, but I had forgotten the details, and of course never knew the story of Hans Paulson. Very tragic.